COM 342, CGD 470, BRiC & the Bauhaus

By #BOCABAUHAUS

How are Lynn University’s courses — COM 342: Advertising and Public Relations Management and CGD 470: Agency Design — similar to workshops at the famous Bauhaus art school, which operated in Germany from 1919-1933?

The following reflects on those Lynn University courses, focusing in particular on their 2022 collaboration with the Boca Raton Innovation Campus (BRiC). Later, this essay will consider how these courses and their work with BRiC relate to both the philosophy of the Bauhaus and to the activities of that school’s advertising workshop.

Additionally, this essay will ruminate on another collaboration between Lynn University and BRiC. In March of 2022, Lynn University opened an off-campus site of its NFT art museum in one of the corridors of BRiC. It is argued that Lynn’s collaborations with BRiC, taken together, invite comparisons with the Bauhaus.

COM 342 & CGD 470: Advertising and Public Relations Management and Agency Design

Lynn students in the Advertising and Public Relations Management course are not just students in a college course; they also become junior account executives in Pulse Agency, a student-run advertising and public relations group. The course is designed to model the real world — to give its students experience much like that working in a professional PR firm.

At the beginning of the course, students meet with an external client — a local business or organization. For the remainder of the course, they develop and then pitch PR campaigns for that client. In past years, students developed PR campaigns for FPL, Town Center Mall, Junior League and Bloomingdale’s, among others. In Spring 2022, the local client was BRiC, an office park in Boca Raton.

Throughout February, students developed proposals for strategic and creative campaigns and developed mock Facebook and Instagram profiles, as well as sample social media posts, emails, event pages and advertisements, among other components. In early March, student groups gave 10-minute presentations, pitching their campaigns to Giana Pacinelli, the Director of Communications for CP Group, owner of BRiC. Each group created its own unique website featuring their work to help with the pitch.

Professors Stefanie Powers and Gary Carlin co-teach the course. Carlin thinks of the course as being a lot like an internship, only without students having to leave campus. In 2022, the course met four days a week for 2.5 hours a day over four weeks. Each day, the professors spent half an hour to an hour on “teachable moments,” focusing on how to develop strong PR campaigns. One day, the class might focus on social media, another day on video and another on writing a press release. After that, for the remainder of each class meeting, students work in groups to develop their campaigns.

The Advertising and Public Relations Management course collaborated with another Lynn course, Agency Design. This course, taught by Professor Scott LeBlanc, is part of the university’s design program and focuses on the visual components of PR campaigns. Several days a week, students from the Agency Design course worked in groups with students from the Public Relations course on PR campaigns for BRiC. They divided responsibilities so students from the Public Relations course focused on strategy and copy while students from Agency and Design focused on visuals.

According to LeBlanc:

The best part of the collaboration with the PR class is that my design students get to experience working with a real client. [T]hey get to work with non-designers … strategists, communicators, writers, social media specialists and marketing students. They experience a dynamic that is … close to a real-world scenario as they will experience in their professional lives.

Two or three times each week, the three professors met with each group of students separate from the rest. The individual groups sat around a conference table with their iPads and discussed with their professors what had been accomplished to that point. The professors asked and answered questions, aiming to steer students in the right direction.

Each group was considered a team, and each team developed a unique PR campaign without knowing what the other teams were developing. After each team pitched its campaign, the client chose a winning proposal. In 2022, the winning team developed a proposal for BRiC, called “Building a Community Through Innovation” with the hashtag #BRICbyBRIC.

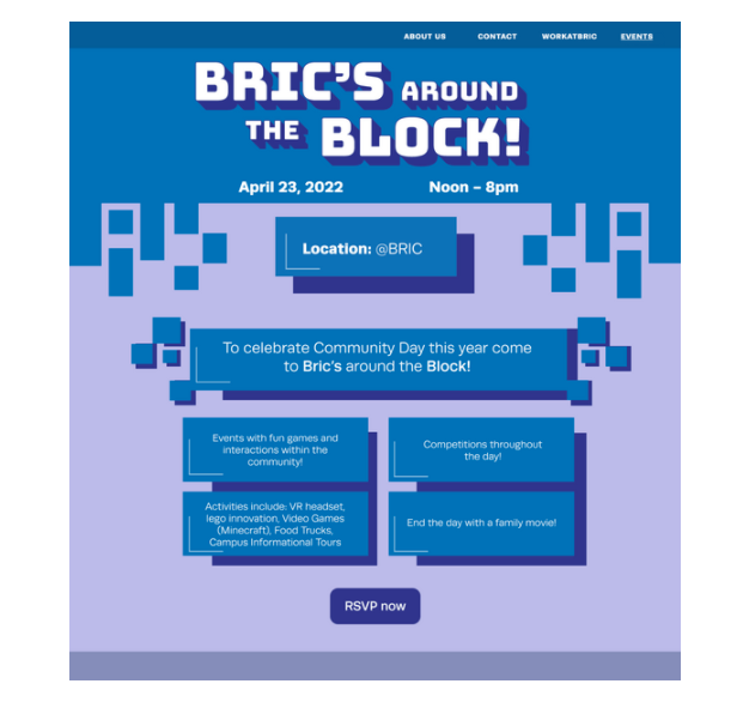

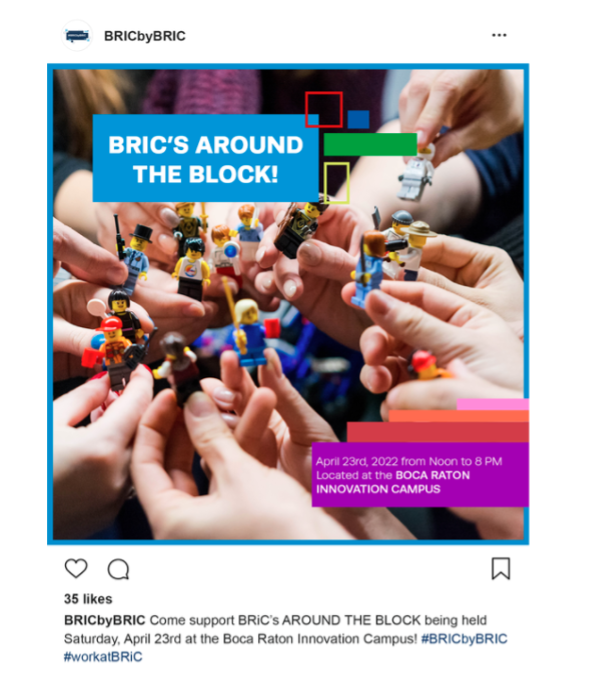

Here are images of two pieces students created for the winning campaign:

COM 342, CGD 470 & the Bauhaus’s Advertising Workshop

The Bauhaus was a famous art school in Germany, which operated from 1919 until 1933. It is well-known principally because its teachers were some of the best artists and graphic designers in the world, including Josef Albers, Herbert Bayer, Wassily Kadinsky, Anni Albers, Paul Klee, Ludgwig Mies van der Rohe, Marianne Brandt, Marcel Breuer, László Moholy-Nagy, Oscar Schlemmer and many others.

At the Bauhaus, students participated in workshops, often completing projects for external clients on commission and crafting goods intended to be sold outside of the school. Students in the Bauhaus advertising workshop created advertisements that were distributed widely and seen by many.

The Bauhaus did not want its students to work in isolation from the outside world. Rather, it wanted students to work on projects for external clients, to develop products they could sell outside of the school and to create prototypes for products that could potentially be mass-produced by industry.

Walter Gropius, the renowned architect and founder of the Bauhaus, remarks that: “The Bauhaus could become a haven for eccentrics if it were to lose contact with the work and methods of the outside world” (as cited in Wingler, 1969, p. 51). Instead, Gropius wanted students to become artists who could work well with outside businesses and industries, and who made products that could sell. According to Gropius, “What is important then, is to combine the creative activity of the individual with the broad practical work of the world!” (ibid., p. 52). Students leaving the Bauhaus would thereby be prepared to work — as artists — in society.

In many ways, Lynn University’s COM 342 and CGD 470 courses resemble the Bauhaus’s printing and advertising workshop. For example, much like Lynn students took an external client, BRiC, the Bauhaus printing and advertising workshop similarly took on commissioned projects from outside clients.

One of the Bauhaus masters who managed the printing and advertising workshop was the graphic designer and artist Herbert Bayer. Bayer or his students accepted commissions to design, among other things, “a folded prospectus for the city of Dessau,” as well as a poster developed “on behalf of the Association for Young Art in Oldenburg” (Rössler, 2014, p. 117). Additionally, they designed “product sheets for the Fagus shoe manufacturer’s fittings” (ibid.).

The Bauhaus printing and advertising workshop advertised itself as a “full-service design shop,” which could produce “printed matter in modern typography” and consult “in new advertising design” (Dickerman, 2009, p. 31). The workshop could also create “publicity materials, business documents … brochures, posters … company logos, trade names, window displays … and advertising photographs” (ibid.). Lynn University’s COM 342 and CGD 470 courses, together, create much the same materials for its clients.

These Lynn courses involve students in hands-on, collaborative projects in which they learn by doing — learn by creating — periodically receiving feedback and guidance from faculty. In the Bauhaus advertising workshop, students learned in a similar manner. Bayer, who managed the workshop, chose not to include many “school-like lessons” in the workshop, instead guiding students through “practical work with technical instruction” (Siebenbrodt & Schöbe, 2009, “Typography/Printing…”; cf. Rössler, 2014, pp. 106-107). The Bauhaus, like COM 342 and CGD 470, wanted its students to learn through experience (Dickerman, 2009, p. 17).

Josef Albers, a famous German artist who taught at the Bauhaus, summarizes a key idea, stating that “We believe in learning by experience, which naturally lasts longer than anything learned by reading or hearing only” (p. 13). Albers added that education “needs more laboratory, studio, and workshop training … It demands direct contact with production and creation” (ibid., p. 14).

Lynn University’s COM 342 and CGD 470, like the Bauhaus, prepare students for post-grad vocation by engaging them in projects completed for the kind of external clients with which they may someday work. And in both Lynn’s courses and the Bauhaus, while students are working on these projects, they are guided by expert instructors who offer guidance and support.

Lynn University’s NFT Museum, BRiC & the Bauhaus

BRiC, a 1.7 million-square-foot office park, is quickly becoming one of Boca Raton’s cultural centers. It has hosted outdoor performances of salsa music and Shakespeare adaptations. It has hosted individual talks and panel discussion with an artist and Florida Atlantic University professor, an engineer who developed early personal computers for IBM in Boca Raton, and leaders in companies like Modernizing Medicine, Magic Leap and Office Depot. BRiC has partnered with the Boca Raton History Museum to create the “History of Tech” museum in its corridors. Finally, it advances an initiative titled “Art on BRiC Walls,” and has “the long-term vision of creating a walking art museum with exhibits throughout its miles of corridors to integrate art and technology into the ecosystem of their campus” (BRiC, 2022). BRiC has also partnered with the Boca Raton Art Museum, which has loaned much of the artwork on its walls. [For more information about the events described here, see: (BRiC, n.d.; 2019a-b; 2021a-d; 2022)].

In March, as part of the “Art on BRiC Walls” initiative, Lynn University opened an NFT museum and fine art museum in a corridor of BRiC. That museum features digital art created by students and faculty displayed on commercial monitors, as well as fine art by Lynn faculty that is hung on the walls (#BOCABAUHAUS, 2022). Lynn’s new museum includes numerous digital artworks that have been transformed into NFTs (nonfungible tokens), unique units of data whose ownership is stored in a decentralized, digital ledger on a blockchain. Drawing on innovations in blockchain technology that were unavailable a decade ago, Lynn’s museum calls attention to relations between art and technology (ibid.).

Similarly, the Bauhaus school emphasized the relationship between art and technology. In 1923, Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius, advanced the slogan: “Art and Technology — A New Unity” (Schuldenfrei, 2009, p. 37; Rössler, 2014, pp. 86-87; Bauhaus Archiv & Droste, 1998, p. 58). Gropius wanted students to become “intimately acquainted with factory methods of production and assembly” (as cited in Dearsyne, 1986, p. 58). Gropius encouraged artists to learn how to work with machines, or at least how to develop prototypes for products that could be mass produced by machines (ibid., pp. 58 & 67). According to Gropius, the machine is “the modern medium of design” (1965, p. 75) — the “vehicle” to realize artistic ideas (ibid., p. 86).

Bauhaus students would become artists trained by the best in the world, yet would also be technologically savvy. Gropius writes, “The Bauhaus wants to train a new kind of collaborator for industry and the crafts, who has an equal command of both technology and form” (as cited in Wingler, 1969). Bauhaus students would therefore be artists who could work and contribute to the modern world, bestowing to it in ways that no one else could. Artists could ensure that machine-made items had not only “beauty of shape and finish,” but also “reality and significance” (Gropius, 1965, pp. 62 & 54).

According to Gropius, only an artist “possesses the ability to breath soul into the lifeless product of the machine, and his creative powers continue to live within it as a living ferment” (as cited in Wingler, 1969, p. 23). The artist’s collaboration “must become an indispensable component in the total output of modern industry” (ibid.). If humans want to make things that exhibit the best combination of “form, efficiency, and economy,” they will need not only the skills of a technician but also the skills of an artist (Gropius, 1965, p. 65).

The Bauhaus wanted to develop students who were not isolated and who could work in the outside world, developing projects related to external businesses and industries, and working with the cutting-edge technology and production techniques of the time. For Gropius, “it would be a mistake if the Bauhaus were not to face the realities of the world and were to look upon itself as an isolated institution” (as cited in Wingler, 1969, p. 51). He adds, “What is important then, is to combine the creative activity of the individual with the broad practical work of the world!” (ibid., p. 52).

There are similar threads in Lynn University’s collaborations with BRiC — including the work of COM 342, CGD 470 and the NFT museum — that highlight a few of the ways in which the university is connected to the surrounding community, to the businesses in it and to the technological advancements of the outside world. Lynn students have developed PR campaigns for BRiC, and their digital artwork has found a home in its halls. Additionally, students in Lynn University’s design program learn how to work with machines — modern computer programs — in the development and production of their art.

These collaborations with BRiC also mean that students’ endeavors belong to something bigger than themselves and bigger than their courses. The efforts belong to a greater society, in which educational institutions collaborate with local business and industry and the technology of the world.

Ribbon-cutting at the opening reception of Lynn University’s NFT and Fine Art Museum at BRiC.

Lynn University, BRiC & the Bauhaus

Gropius hoped students in many workshops at the Bauhaus — aside from the advertising workshop — would work on prototypes for goods that would be mass produced my machines in factories. He writes:

The Bauhaus workshops were really laboratories for working out practical new designs for present-day articles and improving models for mass production . . . Although most of these prototypes had to naturally to be made by hand, their constructors were bound to be intimately acquainted with factory methods of production and assembly. (1965, p. 53; cf. Dearstyne, 1986, p. 58)

Yet, as Robin Schuldenfrei notes, students and faculty from the Bauhaus were only ever able to arrange for a small number of products they developed to be mass-produced by industries (2009, pp. 50-51; cf. p. 38). Bauhaus students and faculty developed lamps that were mass produced and marketed by outside companies (ibid., p. 50; cf. Bergdoll 2009, pp. 52 & 57). The Bauhaus also developed wallpaper that was produced and marketed externally (Bergdoll, 2009, p. 57), as were a limited number of other products.

But most objects designed at the Bauhaus were only ever produced in small batches to fulfill limited commissions (Schuldenfrei, 2009, p. 45 & pp. 47-51). No doubt, by creating objects like this, the Bauhaus accomplished its goal of preparing students to produce goods for the outside community, and prevented students from the kind of eccentric isolation that Gropius feared. But, as Schuldenfrei notes, the Bauhaus never fully satisfied Gropius’s goal of uniting art, business and technology (2009, pp. 37-38). Doing so would have required far more mass production and far greater collaborations between the Bauhaus and machine-based industries than occurred.

A Boca Bauhaus

Now consider Lynn University’s College of Communication and Design in 2022, which focuses primarily on digital products rather than physical ones. Digital products can potentially appear on millions of computers at the same time. This is a form of mass production distinctive from the mass production of physical objects. Consider, too, that Lynn University’s college collaborates with external businesses and industries like BRiC, creating digital content that relates to BRiC and digital artwork that is displayed in its corridors. Might a university program like this successfully unite art, industry and technology, in a way different from what Gropius envisioned (cf. Ehn, 1998)?

Pelle Ehn imagines what he calls a “Digital Bauhaus” — a Bauhaus university program for the modern, digitized world that encourages a “critical and creative aesthetic-technical production orientation that unites modern information and communication technology with design, art, culture, and society” (Ehn, 1998, p. 2010). Ehn provides an extensive account of the sort of program he envisions. This essay does not claim that Lynn University’s program captures Ehn’s vision; though it is, at least in some ways, related. Instead, this essay reflects on Lynn University’s collaborations with BRiC, like the NFT museum and the collaborations between BRiC and COM 342 and CGD 470, wondering if these collaborations might be the beginning of, if not a Digital Bauhaus, then — perhaps — a new Boca Bauhaus.

Perhaps BRiC is the most suitable partner for a venture like this, being committed to collaboration with local organizations and universities like Lynn, the Boca Raton Art Museum and the Boca Raton History Museum. And BRiC, which hopes to attract technology tenants (BRiC, 2021a), values the prospect of uniting art and technology. As noted, it hopes to create in its corridors both a “History of Tech” museum and also an extensive walking art museum, with hundreds and perhaps thousands of quality artworks.

Likewise, the main buildings at BRiC were codesigned by a former Bauhaus teacher. Marcel Breuer, the architect who codesigned the buildings that are now part of BRiC, studied at the Bauhaus when Gropius advanced the slogan “Art and Technology: A New Unity.” Later, Breuer became a master teacher at the Bauhaus. While there, he designed numerous pieces of furniture, utilizing then cutting-edge technology, which subsequently were mass produced in great quantity by factories using machines.

Breuer originally designed the buildings in Boca Raton for the IBM corporation, which owned them long before BRiC. He designed the buildings — themselves a work of art — for a company that mass produced computers and advanced technology. Thus, the buildings at BRiC represent the unity of art and technology.

Lynn University’s College of Communication and Design focuses heavily on digital advertising, digital art and digital PR, and so it approaches the goal of uniting art and technology. BRiC is similarly committed to the unity of art and technology and its buildings were born out of the work of a Bauhaus master. Might collaborations between the two herald the beginning of a new Boca Bauhaus?

BRiC hosted a public event in which artist and FAU professor Carol Prusa discussed “The Intersection of Art and Tech.” At that event, Angelo Bianco, the managing partner of CP Group, which owns, develops and manages BRiC, remarked:

We focused on something that is dear to my heart, and I know yours, and that is art and technology … We believe that the confluence of these two ideas create the most beautiful projects … I wanted to leave you with a quote from … Albert Einstein. He said, ‘After a certain high-level of technical skill is achieved, science and art tend to coalesce in esthetics, plasticity, and form. The greatest scientists are always artists as well.’ (as cited in BRiC, 2020)

A building, at BRIC, designed by the former Bauhaus teacher Marcel Breuer.

References

Albers, J. (1969). Search versus re-search. Trinity College Press.

Bauhaus Archiv & Droste, M. (1998). Bauhaus: 1919-1933. Benedict Taschen.

Bergdoll, B. (2009). Bauhaus multiplied: Paradoxes of architecture and design in and after the Bauhaus. In B. Bergoll & L. Dickerman (Eds.), Bauhaus 1919-1933: Workshops for Modernity (pp. 40-60). The Museum of Modern Art.

#BOCABAUHAUS. (2022, March 10). Lynn University’s NFT Museum at the Boca Raton Innovation Campus. iPulse. http://lynnipulse.org/archives/10924

BRiC. (n.d.). Welcome to BRiC: The office part of innovation. http://workatbric.com/

BRiC. (2019a). Finding the ‘I’ in AI. https://workatbric.com/event/ai-transforming-business-in-partnership-with-tedxboca

BRiC. (2019b). Intersection of art & tech. https://workatbric.com/event/intersection-of-art-tech

BRiC. (2020, January 13). Intersections between art & tech [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xBudlmhY2Xw

BRiC. (2021a). Welcome to Boca Raton Innovation Campus [PowerPoint slideshow for BRiC Master Plan Group Tour]. Undistributed.

BRiC. (2021b). Boca Raton Innovation Campus [Brochure]. https://workatbric.com/app/uploads/2021/02/BRiC_Brochure-2021.pdf

BRiC. (2021c). BRiC LIVE summer performance series. http://workatbric.com/event/bric-summer-performance-series-brazilian-nights/2021-07-29

BRiC. (2021d). Boca Raton tech talks. http://workatbric.com/event/boca-raton-tech-talks/2021-03-02

BRiC. (2022). Art on BRiC walls. https://bocamuseum.org/art-bric-walls

Dearstyne, H. (1986). Inside the Bauhaus (D. Spaeth, Ed.). The Architectural Press.

Dickerman, L. (2009). Bauhaus fundamentals. In B. Bergoll & L. Dickerman (Eds.), Bauhaus 1919-1933: Workshops for Modernity (pp. 14-39). The Museum of Modern Art.

Ehn, P. (1998). Manifesto for a digital Bauhaus. Digital Creativity, 9(4), 207-217.

Gropius, W. (1965). The new architecture and the Bauhaus (P.M. Shand, Trans.). The MIT Press.

Rössler, P. (2014). The Bauhaus and public relations: Communications in a permanent state of crisis. Routledge.

Schuldenfrei, R. (2009). The irreproducibility of the Bauhaus object. In J. Saletnik & R. Schuldenfrie (Eds.), Bauhaus Construct: Fashioning Identity, Discourse and Modernism (pp. 37-60).

Siebenbrodt, M. & Schöbe, L. (2009). Bauhaus: 1919-1933 Weimar-Dessau-Berlin. Parkstone International.

Wingler, H. M. (1969). The Bauhaus: Weimar Dessau Berlin Chicago. The MIT Press.